Understanding the prospects of robot programming and cultivating logical thinking

Outline of the article: – Foundations and mental models for robotic behavior; – Languages and architectures spanning low-level control to high-level orchestration; – Perception and decision-making under uncertainty; – Safety, testing, and quality assurance; – Learning pathways and career prospects that cultivate logical thinking.

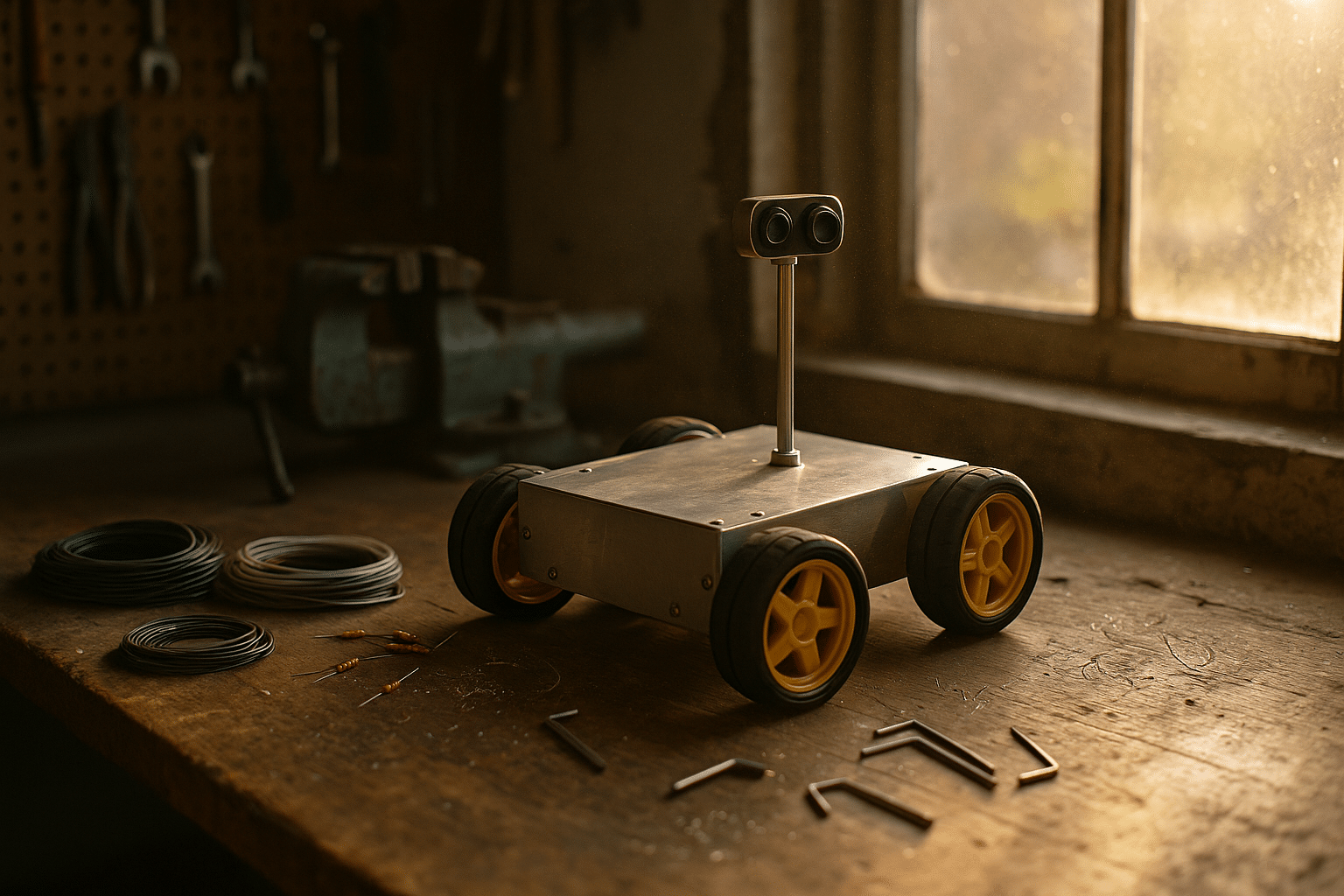

Robots are less about bolts and more about ideas: how to perceive, decide, and move through the world safely and reliably. Programming them amplifies logical thinking because it forces clarity in goals, structure in decisions, and discipline in testing. Industry surveys consistently report rising deployments across manufacturing, logistics, agriculture, and service settings, and that momentum is sustained by software skills that generalize across platforms and domains. Whether you are building autonomous carts, precision pickers, or classroom projects, the same principles apply: model reality, plan actions, measure outcomes, and iterate with care.

The Logic Behind Motion: Core Concepts and Mental Models

At the heart of robot programming lies a simple loop with deep consequences: sense, think, act. The robot samples the environment, selects an action based on objectives and constraints, and executes a motion that influences the next round of sensing. This feedback cycle is where logical thinking sharpens, because even small mistakes in assumptions can multiply across time steps. A practical mental model begins with goals, measurable states, and clear transitions between states. For example, a mobile platform may define states such as “idle,” “navigating,” “avoiding,” and “docked,” with conditions to move between them. This prompts questions like: What measurements confirm docking? What thresholds trigger avoidance? How do we handle ambiguous sensor readings?

Geometric reasoning gives these states a body. Coordinate frames describe positions and orientations, while degrees of freedom define how joints or wheels can move. Kinematics maps desired end-effector positions to joint angles, and dynamics accounts for forces, inertia, and friction. Planning algorithms explore the space of possible actions while honoring constraints like joint limits and collision avoidance. In practice, programmers must navigate trade-offs: a fast but coarse planner may be sufficient for repetitive tasks, while cluttered, changing environments may demand slower, more deliberate search with frequent re-planning.

Time adds another dimension. Discrete control cycles sample and command at fixed intervals, creating a dance between precision and stability. Too slow, and the robot lags; too fast, and noise dominates. Logical thinking helps frame these choices with guardrails such as: – Define update rates based on actuator bandwidth and sensor latency; – Set safety margins for braking distances; – Use state estimates that quantify uncertainty rather than single-point guesses. Even without heavy math, writing pseudocode that separates sensing, estimation, planning, and actuation builds mental clarity. This separation also prepares the ground for tests that isolate failures to a specific layer, turning complex behavior into manageable, verifiable parts.

Languages and Architectures: From Low-Level Control to High-Level Behavior

Robot code spans a spectrum. At one end, low-level loops generate motor commands at predictable intervals, often in compact, efficient languages tuned for real-time constraints. At the other, high-level scripts express tasks in human-friendly terms like waypoints, pick-and-place sequences, or assembly workflows. Between these poles sit domain-specific notations and graphical tools such as ladder diagrams, function blocks, and structured text, which are common in automation. Each layer serves a purpose: low-level control offers timing precision; mid-level logic coordinates sensors and actuators; and high-level orchestration captures intent.

Choosing a language or representation is a matter of context. Text-based code excels when you need abstractions, modules, and testing frameworks. Graphical logic is convenient for technicians and for quickly mapping interlocks, alarms, and state transitions. Teach-by-demonstration is appealing on the factory floor, where an operator can jog a manipulator to key poses and store trajectories as reusable programs. Offline programming, in contrast, lets teams design and simulate complex cells before hardware exists, reducing commissioning time. These options are complementary rather than competitive; many workflows blend them to balance speed, clarity, and maintainability.

Architecture matters as much as syntax. A component model with message passing encourages loose coupling: – Sensors publish measurements at their natural rates; – Estimators fuse data and output state; – Planners generate goals; – Controllers track targets; – Supervisors handle errors and mode switches. Such designs enable modular testing and reuse across projects. For instance, a path planner for a mobile base can be reconfigured to guide a warehouse cart or a farm rover with minimal changes to surrounding code. When comparing approaches, consider observability (what can be measured), controllability (what can be commanded), and diagnosability (how quickly faults are isolated). Favor patterns that make failure transparent, because clarity during troubleshooting often determines uptime more than raw algorithmic elegance.

Perception and Decision-Making: Sensors, Learning, and Uncertainty

Robots engage the world through imperfect senses: depth cameras, inertial units, encoders, sonars, and other modalities each provide partial truths. Sensor fusion estimates the hidden state—pose, velocity, object positions—by combining complementary strengths and filtering noise. Classical estimators deliver consistent results when models are accurate, while data-driven models can generalize from examples when physics is hard to write down. In practice, successful systems mix both: physics anchors behavior in predictable regimes, and learning fills gaps where models are brittle.

Vision is a revealing case. Traditional pipelines detect edges, lines, and shapes to infer geometry, and they run efficiently on modest hardware. Learned detectors recognize categories and poses directly from examples, handling clutter more gracefully when trained well. The trade-offs involve data and drift: labeled examples require effort to collect, and domain shifts (lighting, backgrounds, new parts) can erode performance. Pragmatic strategies keep perception honest: – Calibrate sensors regularly and log metrics like detection confidence; – Use synthetic variations during training to improve robustness; – Gate decisions with sanity checks, such as rejecting grasp targets that violate reach limits; – Escalate to human review in rare, high-stakes cases.

Decision-making sits upstream of motion. Finite state machines are straightforward and auditable, ideal when tasks are well-structured and failure modes are known. Behavior trees bring flexibility, enabling fallbacks and retries without spaghetti logic. Optimization-based planners evaluate many options simultaneously but need careful cost design to avoid surprising choices. In uncertain environments, the robot benefits from explicit risk handling: – Assign penalties for near-obstacle trajectories; – Prefer actions that keep sensing rich and future choices open; – Slow down when confidence drops. Reports from multiple sectors indicate that autonomy succeeds when systems admit uncertainty rather than hide it, measuring confidence and adapting policy on the fly.

Safety, Testing, and Quality: Building Trustworthy Robots

Safety is not a feature you bolt on at the end; it is a design posture that influences every line of code. Risk assessment starts with identifying hazards: pinch points, high speeds, sharp tools, electrical risks, and unintended motion. For collaborative scenarios, separation monitoring and speed limits reduce exposure, while physical guards and interlocks remain the backbone of traditional cells. Software complements hardware by enforcing safe states, graceful degradation, and clear recovery steps. A simple rule of thumb is to define a “safe stop” pathway early and verify it often, including how the robot behaves after power cycles or sensor faults.

Testing must mirror reality, which is messy. Simulators accelerate development by letting teams rehearse thousands of scenarios without risking equipment, but fidelity varies, and overfitting to a digital twin can backfire. A balanced approach layers tests: – Unit tests confirm math and message formats; – Integration tests verify timing and resource usage; – Hardware-in-the-loop exposes drivers to real signals; – Field trials assess edge cases like dust, glare, and vibration. Logs and telemetry are invaluable; they turn gut feelings into measurable trends, flagging regressions before customers do. Version control, code reviews, and coding standards may sound mundane, yet they often prevent the most disruptive bugs: off-by-one errors, unhandled exceptions, and race conditions.

Reliability also means thinking about maintainability and observability. Clear diagnostics codes, bounded retries, and consistent startup sequences help technicians recover quickly. Configuration management deserves attention: a mislabeled frame or swapped cable can mimic a logic bug for days. Document assumptions in the code near where they matter, not in distant manuals. Finally, recognize that many safety incidents stem from interaction effects rather than single component failures. Designing for layered defenses—procedural checklists, protective stops, watchdog timers, and conservative defaults—creates resilience. Evidence from deployments across sectors shows that disciplined testing practices shorten ramp-up time and reduce downtime, improving both safety and productivity without glamor or hype.

Learning Pathways and Career Prospects: Cultivating Logical Thinking

Getting started does not require a warehouse full of hardware. A practical path begins with simulation and small electromechanical builds, then graduates to integrated projects. Begin by writing simple programs that blink LEDs, read sensors, and drive small motors; these introduce timing, interrupts, and control loops in a forgiving setting. Next, compose behaviors: line following, obstacle avoidance, and docking. Keep a lab notebook with measurements and sketches of state machines. This habit converts tinkering into experiments and turns results into reusable knowledge.

As skills grow, tackle projects that surface realistic constraints: – Build a pick-and-place demo that handles varying object positions; – Program a mobile base to navigate around moving obstacles; – Integrate a camera to estimate pose and verify grasp success; – Add a dashboard with logs and status indicators for remote supervision. Along the way, learn to read datasheets, tune controllers, and profile code. Practice writing clear requirements—what the robot must do, how success is measured, and what happens when sensors fail. These habits cultivate logical thinking that transfers to other fields like embedded systems, data engineering, and operations.

Career prospects span many roles. Integration engineers bring robots to the shop floor and refine them during commissioning. Application developers craft reusable toolkits and templates for common tasks. Perception specialists improve sensing and estimation, while reliability engineers focus on testing pipelines and observability. Educators and mentors are equally vital, translating complex ideas into accessible projects for classrooms and community labs. Market analyses consistently report steady growth in automation, with annual installations in the hundreds of thousands and expanding demand beyond heavy industry into logistics, agriculture, and service work. For learners, the signal is clear: fluency in modeling, planning, and testing opens doors. More importantly, the mindset you develop—breaking problems into parts, checking assumptions, and measuring outcomes—serves as a compass for lifelong learning.

Conclusion

Robot programming rewards those who value clarity over flash and process over shortcuts. By mastering core loops of sensing, planning, and acting—and by treating safety and testing as first-class citizens—you cultivate logical thinking that travels well across careers. Start small, iterate deliberately, and keep your eyes on measurables; the skills you gain will compound as automation continues its steady march into everyday environments.